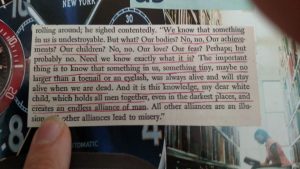

This is an image from a collage I made (entitled “How Not To Die”) and shows a quote from Frederic Prokosch’s Storm and Echo (1948) and like many moments in his work, it touches something in me at a depth I often forget exists.

Prokosch published his first novel The Asiatics, about a young man’s picaresque journey through Asia, in 1935, to critical and financial success. He received acclaim from such contemporaries as Camus, Hemingway, and Andre Gide.

The remarkable thing about the book (aside from it’s beautiful language and quickly moving narrative) is that Prokosch had no first-hand knowledge of any of the places he wrote about. Even so, his attention to detail and authority on the page convinced readers and critics that had been to these places. Now, it is arguably a period piece, offering a westerner’s view of Asian culture from this time period (more than a few contemporary readers have taken offense at the cultural descriptions). Perhaps this was somewhat purposeful on Prokosch’s part and he is trying to make a statement about western ethnocentrism, perhaps it is a reflection of the time. Either way, I choose to view the work more as a fantasy, symbolic of a more archetypal or spritual journey. Through this lens, “the other” is always a friend with strange wisdom to assist the hero, or else a sinister villian with a vital lesson (Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey/Jungian archetypes). And while Prokosch was meticulous using maps to recreate accurate geography and topography, the descriptions of the terrains often take on a fantastical quality, becoming an almost mental or spiritual landscape.

The Seven Who Fled was his second novel, covering much of the same ground, literally and allegorically. The difference is it’s longer and each section follows a European from a different country in their flight through Asia. It is a better book than Asiatics in terms of lyrical power and the sheer expanse of its vision, but ultimately a slower moving and longer read.

After these novels, Prokosch had very little success, despite at least 16 credited novels and 5 or more collections of poetry. His third book, Night of The Poor was an American Asiatics. Critics panned it for its two dimensional characters and, ironically, what with Prokosch being born and educated in the US, inaccuracies, especially flora and fauna. Of his books that I’ve read, it seems he largely sought to recreate the Asiatics over and over again. Nine Days to Mukallah is the Arabian version and Storm and Echo (see above image and quote) is the African. While Night of the Poor is pretty awful, I think these last two retain much of the charm and lyrical power of the first two novels. Storm and Echo, while not the first or the best, is my favorite.

His later novels experimented with genres, such as horror and the gothic, and even magical realism. America, My Wilderness, his only other novel set in America, manages something closer to success at what he likely was aiming for with Night of the Poor. America, My Wilderness was so strange and full of carnival-like characters and setting, the magical realistic elements are far cannier than they would be otherwise. It is definitely one of his most interesting reads, and of a caliber with his better work. It is arguable though that of all the places in the world Prokosch lived, his native land was the one with which he had the most tenuous understanding.

His best late book is The Missolonghi Manuscript, a recreation of Lord Byron’s journal and memoirs from his final days as a leader in the Greek army. Meticulously researched, it is clear Prokosch identifies with the romantic poet, not only in sexuality (both had male partners) and predisposition to verse (I wonder if Prokosch’s tendency to rehash theme might not be an attempt to finance his verse), but also in that both are individuals, completely distinct from anyone else in literary history.

From early on in his career, Prokosch was an expatriate and traveled widely, particularly in Europe, but eventually all over the world. After his initial success, he was often short on money. His poetry, from the beginnng, was influenced heavily by Auden, and at a particularly desperate stage of his career, he sold broadsides he had forged and attributed the work to the more famous poet. There was also scandal surrounding his 1984 memoir of his meetings with various literary influences, including Thomas Mann, Gertrude Stein, Hemingway, Wallace Stevens, and many more. Much, if not all of it, was fictionalized.

Personally, I read the memoir prior to knowing this and it quickly was clear to me that the way the authors were presented were homages and cariactures based on their work. It is strange to me that they would have been taken seriously as nonfiction to begin with.

All told, Prokosch is a relatively unknown writer that is worth revisiting because of his imagination and lyrical talents. The narratives around the stories and the scandals don’t have to intrude on the value of the work. In fact, they may add to them in a way that few authors’ biographies do. It is a common assumption in literary theory that all narrative provides a fictional frame, even when it is entirely factual. There is always the subjectivity inherent in the perspective from which the facts are recounted or perceived. Further, no word is the thing itself, it is a representation of the thing and carries all personal and public contexts with it when that word is used to describe the thing in actual. This is the grand spiritual trancendence pointed to by fiction itself: that truth is not derived from fact, but rather an intuitive understanding of beauty in it’s relation to reality. Prokosch proves this hypothesis for us – in his lyricism and his vision – but also his identity, which itself exists in the ether of story.