ONE.

You used to have cross over railroad tracks to get here. Now, there’s town houses where the road used to end abruptly into mud and gravel. A bike path with joggers and young mothers pushing strollers. A bridge over the tracks enclosed by chain link to prevent you from jumping the train, a boardwalk leading up and down either side.

All the old themes get exhausted, turned into theme parks.

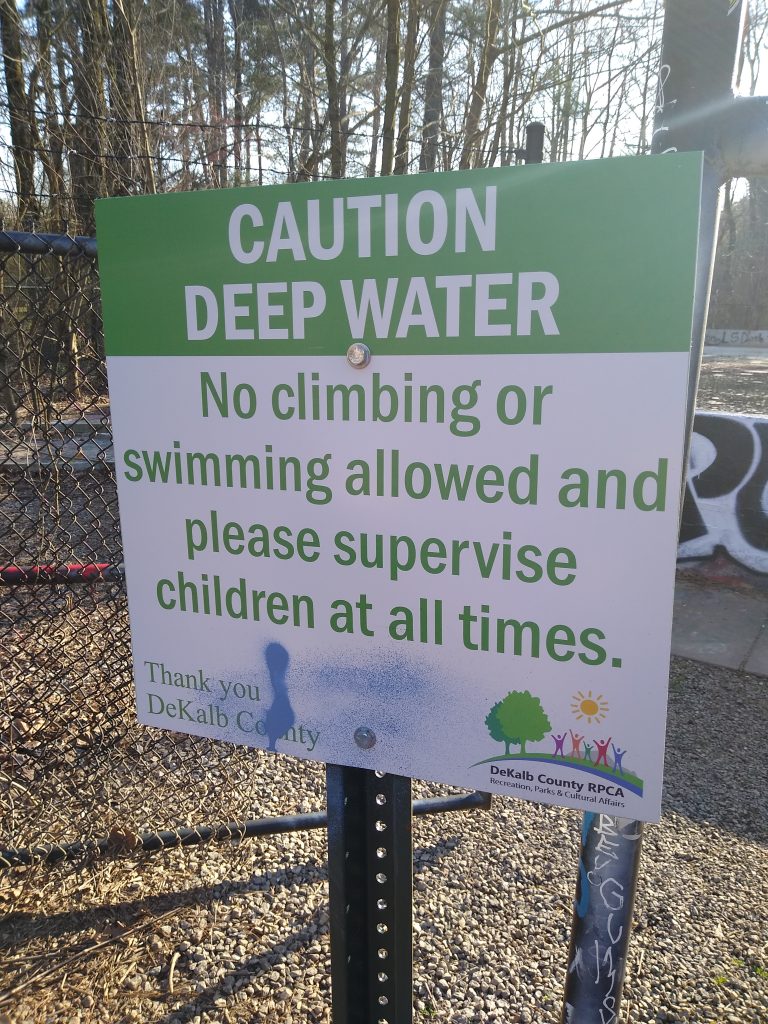

The ruins are still there though. A beaten path makes a b-line off the bike path, through some tall grass and weeds. Some bush and low hanging branches still there, but trimmed back so the way is not impeded. The way leads down into a gulley, the remains of concrete structures on either side, wild with impromptu murals and other graffiti.

Now, two old friends cross the creek that parallels the path into the gulley. They stand in the center of the place where once they made fires at night and told stories among the ruins. There’s still a door in a collapsing wall that leads to nowhere. You pass through it to the former lives of strangers. They would take any one of the winding paths out into the dark wooded brush, sit and watch the ghosts of mill workers moving about the outskirts of the ruins. Now, there are flesh and blood people here, clad in street clothes, but with surgical masks to prevent the spread of disease.

A Japanese man takes a picture of his wife in front of a wall that reads EGO in bright barely legible angles that are part of its design. Two young men, Spanish-speaking, climb a ruined wall to walk foot over foot along the wall like a high wire. One stutters, nearly falls into the open mouth of the structure.

Our lives flash before our eyes.

TWO.

The adjacent park used to be cutoff from the ruins. The risk of disease used to just be part of going out. Things are different now. We all wear masks.

It is what it is, isn’t that what they say.

Now, the bike path leads all the way back to the tennis courts. The children’s playground has been fenced off due to the pandemic. A little boy, clenching his fists, says: I could kill them if they were here.

Who, sweetheart? his mother says. Don’t talk that way.

The ones who put up the walls, he says.

He stands facing the fence, his arms reached out above him, fingers hanging from the links.

Sometime later, he will be laughing and chasing his little sister in the grass, playing some sort of game where the sidewalk is electric. A boundary to keep them from getting to close to the street.

In the parking lot, two women, somehow related, are saying goodbye at their cars. One seems younger, in her 30s, maybe, with brown hair. The other is not quite old, but older, and her hair pulled back is silver.

I wish I could hug you, the woman with brown hair says.

It won’t be forever, says the woman with silver hair.

And the younger woman takes a step toward her, arms outstretched, like maybe she will give her some sort of distant hug, or maybe she will risk it and take the other woman in her arms. I don’t know. The younger woman’s arms outstretched was the last thing I saw before I turned to go.